Wasting Away

How the Keep America Beautiful Campaign Helped Uglify America and What We Can Do About It Now

by Torrey Douglass

As a child of the 70s and 80s, I grew up seeing ad campaigns from the Keep America Beautiful® (KAB) organization on billboards and TV. I encountered its logo on soda bottles and posters, imploring us to pick up our trash. The group first began to spread its anti-litter message in the early 50s and was originally represented by its first spokes-hero, Suzy Spotless, a cutiepie little girl, dressed immaculately in white, who threw garbage into trash cans under the tagline, “Every Litter Bit Hurts,” in a tone that was equal parts simpering and scolding.

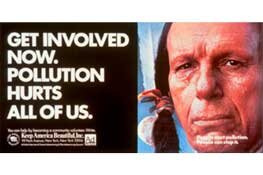

By the time the 70s arrived, ads with Ms. Spotless weren’t packing the same cultural punch, so the (in)famous “Crying Indian” campaign was created, featuring “Iron Eyes Cody,” a popular Western film star of the day. In the commercial spot, the Italian-American actor, dressed in Native American garb, encounters pollution everywhere—cluttering the stream that carries his canoe, belched into the air by the factories he passes, and thrown out of car windows to sully the ground around his moccasins. Litter is caused by people and can be stopped by people, the message says. Stop making noble Mr. Indian sad. Clean up your crap.

Always a bit of a wild child, I preferred climbing trees or tunneling into the depths of a forsythia bush in full bloom to any indoor endeavor. So when I saw ads produced by KAB, I was entirely on board. The idea that we don’t want garbage tarnishing nature’s glory resonated deeply. I wanted to keep America beautiful. I wanted to do my part. Litterbugs were the worst, I silently agreed, whenever KAB messages found their way to me.

What I didn’t realize then but understand now is this: Keep America Beautiful was the outcome of beverage and plastic companies fighting back against pressures to hold their industry accountable. While they had formerly used glass bottles that were returned and re-used, beverage companies had shifted to single-use containers as part of a post-war push to maximize consumerism, and there was a corresponding spike in trash besmirching America’s landscapes. American Can Company, Owens-Illinois Glass Company, Coca-Cola, and the Dixie Cup Company came together to create KAB after Vermont passed a law prohibiting these “throwaway bottles” in 1953, a law made because glass shards from bottles thrown from passing cars were endangering the cows grazing in roadside pastures.

The legislation sent shivers through the beverage industry, and they answered anonymously from behind the guise of KAB. Powerful ad campaigns labeled the waste as “litter” and the culprits as “litterbugs,” consumers who purchased their products but didn’t manage the resulting trash properly. The same organization that created the scolding or heart-tugging ads about the terrible problem of waste pollution was simultaneously lobbying hard against any bills that would force manufacturers to adjust their central role in the litter’s production.

The planet has paid a price for the KAB’s successes, giving plastic producers free reign to generate packaging that is used once, and then haunts our seas and landfills for centuries. And they are not slowing down. Half of all plastic waste in existence has been produced since 2005, and only 9% is ultimately recycled. The remaining plastics—50% of which is food and drink packaging—can break down into microscopic pieces that enter the foodchain and end up in our food and water—and, consequently, inside of us. According to a study by the World Wildlife Fund and executed by the University of Newcastle, Australia, people consume about a credit card-worth of plastic each week. Suzy Spotless would not be pleased.

Yet there are ways to pressure producers to address the problem, with many developed countries and some U.S. states adopting Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) laws, compelling companies to reckon with the waste their products ultimately become. But industry lobbyists continue to push back against EPR laws, fiercely defending those sweet, sweet profits that single-use packaging enables. In light of their reluctance, downstream participants in the lifecycle of packaged foods and beverages can and are taking action, from the retailers that carry the products to the consumers who buy them.

the bulk food section at Ukiah Natural Foods Co-op

Ukiah Natural Foods Co-op has been working hard to reduce their role in contributing to the global problem of accumulating plastic waste. Their efforts go right back to the store’s roots as a buying club, when members came together to purchase in bulk in order to, among other goals, reduce the packaging that contained their food purchases. While a number of their measures have been suspended due to the COVID pandemic, manager Lori Rosenberg hopes to reinstate and exceed their waste-reduction actions once it’s safe to do so.

These efforts span all departments, from the paper and cellophane bags the deli uses for sandwiches in place of plastic wrap, to the collection of leftover juice pulp and produce clippings, which are passed along to local farmers for feed and compost. Styrofoam pellets are saved for a local pack and ship shop that uses them to send parcels, and unsellable foods are donated to Plowshares. The Co-op even sent letters to independent vendors a few years ago, asking them to stop using styrofoam pellets and to instead package their goods in recycled paper or cardboard. Many agreed and adjusted their shipping practices, and some even sent letters of thanks for the initiative.

Of course, customers are encouraged to bring their own bags and can even bring clean containers from home to fill with bulk items like dry goods, honey, oils, and even some beauty items like shampoo and conditioner. But there’s still a long way to go. Pallets are returned to distributors for reuse, but the shrink wrap that secures boxes to them continues to end up in the dumpster. The store offers over 25,000 products, many of which are packaged in plastic. “I wish there were programs to recycle all this plastic,” says Rosenberg. “There just has to be a way.”

When seeking solutions for such a complex problem, the approach must be multifaceted. Yes, consumers must reduce their consumption of plastic-packaged goods where possible and maximize recycling where they can (see sidebar for suggestions). Yes, stores and other retailers should prioritize products with reusable or eco-friendly packaging. And yes, producers need to finally own their role as the source of this problem, abandoning the high-hype/low-results initiatives they’ve pursued in the past and instead pursue solutions that actually reduce the planet’s overabundance of plastic waste.

American individualism has some admirable components, but the fact stands that we can achieve more collectively than we can individually, and legislation is the most effective expression of collective will. Laws that force food and beverage producers to take responsibility for their single-use packaging would have the greatest impact in stemming the tide of plastic waste. Some of that plastic ends up in our oceans, and if we do nothing, the weight of ocean plastic will exceed the weight all the fish in all the seas by 2050. Let’s do all we can, personally and legislatively, to put our planet on a different path, so tomorrow’s wild child will have their own beautiful natural spaces to explore.

Sidebar: What You Can Do

Opt for glass jars instead of plastic wherever possible—and be sure to reuse or recycle them!

Bring your own bags when shopping, and use your own coffee mug and water bottle when sipping away from home.

Avoid “wish-cycling”! Make sure you understand recycling rules, as deliveries contaminated with non-recyclables are sent to the landfill. Plastic companies have co-opted the triangle arrow symbol, insisting it appear on all plastic containers regardless of their recyclability. To be safe, only add clean plastic labeled 1 or 2 to your recycling bin.

Compost your food waste.

Carry reusable utensils with you so you can skip the one-use plastic versions when getting take-out. On their website, MendoParks offers a bamboo set that is both light and attractive.

Avoid plastic packaging when you can, like the molded plastic clamshells holding a bunch of apples, and let the retailer know that packaging affects your purchasing choices.

Encourage your elected representatives to support EPR bills to address the problem of food packaging waste at its source.